"I remember thinking to myself, well they have to be really intelligent you know to be able to work on those cars and not only work on those cars but actually be able to be faster than everybody else and win races."

Cristina Mañas Fernández was just a young girl watching Fernando Alonso race in his Renault when she first glimpsed the world she'd eventually inhabit. Today, as Nissan Formula E's head of performance and simulation, she's living proof that motorsport careers can begin from the most unexpected places – in her case, volunteering as a marshal at the last race of Formula E's second season in London.

What makes Cristina's journey particularly fascinating isn't just the career progression from marshal to team leader, but how her story illuminates the unique technical challenges facing Formula E engineers. As someone who's spent years analysing racing performance, I find the evolution of electric motorsport engineering absolutely captivating – and Cristina's insights reveal just how different this world is from traditional Formula 1.

The Correlation Challenge: When Street Circuits Change Everything

London Formula E street circuit

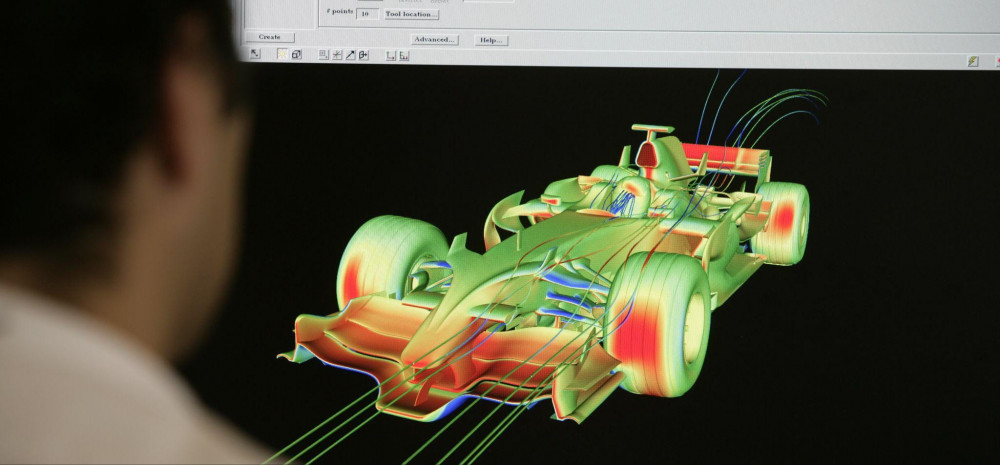

The biggest technical hurdle in Formula E isn't what you might expect. It's not battery management or regen strategies – it's correlation. "When they build up tracks in the middle of cities which are built kind of like a week before we get there, they cannot always be put together as you thought that was going to be," Cristina explains.

This creates a nightmare scenario for simulation engineers. Imagine spending weeks preparing your virtual model of a circuit, running countless simulations with your drivers, optimising setup and energy management strategies – only to arrive at the track and find the surface grip is completely different, or that a corner radius has changed by mere centimetres.

As a driver myself, I know how critical track-specific setup is. In Formula 1, teams have decades of data from established circuits. In Formula E, you're often working with assumptions that can prove catastrophically wrong within the first practice session. Cristina's team at Nissan maintains up to six engineers back at the factory specifically to tackle this correlation nightmare, ready to "almost redo a fair amount of simulations" when track reality doesn't match virtual expectations.

This level of uncertainty would terrify most F1 performance engineers, but it's become the norm in Formula E. The ability to adapt quickly isn't just an advantage – it's essential for survival.

Data Science Revolution in Small Teams

Here's where Cristina's story gets really interesting from a technical perspective. Faced with mountains of telemetry data but lacking the extensive software departments that F1 teams enjoy, she did what any resourceful engineer would do – she built her own tools.

"When you need something actually you've got to do it yourself because you don't really have a software team that you can go ask for something and you have it a week after," she recalls. During the COVID lockdown, Cristina taught herself programming to create data analysis tools that would eventually become the foundation of Jaguar's data science group.

This speaks to something I've observed throughout motorsport: the best engineers don't wait for perfect tools – they create solutions. Cristina defined the specifications herself because she knew she'd be the end user. This hands-on approach to tool development meant the software evolved exactly as the performance engineers needed it to, without the communication gaps that often plague larger organisations.

The result? More efficient data processing that allows small Formula E teams to extract maximum value from every byte of telemetry. "We decided that actually there was probably a space to create a group out of that and it became what we call data science group which should basically be a group that would be looking at how we can use in an efficient way the data that we had available in the team."

Race Weekend Intensity: Every Hour Counts

Cristina's description of a Formula E weekend reveals just how compressed everything becomes when you're operating with smaller teams. The timeline between practice and qualifying is brutal – "probably the most intense hour of the weekend" where engineers must rapidly analyse practice data, identify limitations, and implement solutions before qualifying begins.

Typical race schedule

"If one driver's got you know five things that you'd like to address, which are the top three that can gain us the most performance? We'll focus on them, make sure that they are where they need to be for quali."

This prioritisation under extreme time pressure is something F1 engineers face too, but the smaller Formula E teams make every decision more critical. There's no army of specialists to delegate to – often, the performance engineer looking at aero balance is the same person who'll be checking energy management strategies and tyre allocation.

The knock-on effect of qualifying performance adds another layer of complexity. Make it through to the duels, and your race preparation time shrinks dramatically. "The farther you make it in the duels, the less time you've got to prepare for the race." It's a high-stakes balance between qualifying performance and race preparation that would make even seasoned F1 strategists sweat.

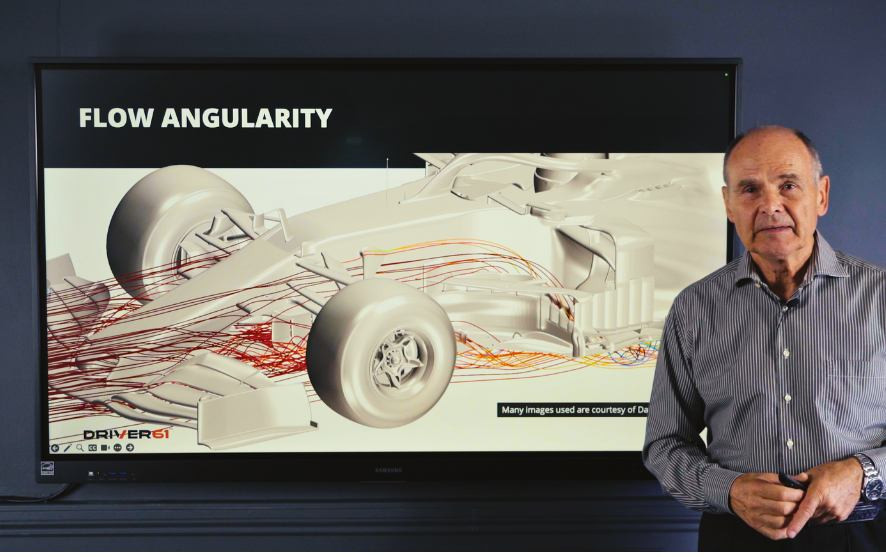

Performance Engineering: F1 vs Formula E

Having worked in both series through my training and analysis work, I can appreciate Cristina's observation that "performance engineering in Formula E is already different [from] what a performance engineer in Formula 1 or any other category can be."

In F1, a performance engineer might focus solely on aero balance or suspension geometry. In Formula E, you're dealing with energy management, attack mode strategies, and traditional vehicle dynamics all wrapped into one role. It's like being a Swiss Army knife in a world of specialist precision tools.

Cristina at work

Cristina's career progression from simulator development to trackside performance engineering to data science leader illustrates this perfectly. "Being a small team means that you can actually get to see many different areas because in fact [a] less amount of people's got to cover up for [a] larger amount of tasks." In F1, such moves between disciplines are less common due to the specialisation required. In Formula E, adaptability and broad technical knowledge often trump deep specialisation.

The Future: Gen 4 and Beyond

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Cristina's current role is straddling present and future. As head of performance and simulation, she oversees four different groups of engineers under one umbrella – performance engineers, energy management engineers, simulation, and simulator specialists.

"Today we've got a season that started a few months ago but we are already designing ahead of the Gen 4 that Nissan has signed up for," she explains. This dual timeline approach requires engineers to optimise current performance whilst developing future technology simultaneously.

From a driver's perspective, this continuous evolution is what makes Formula E so exciting. The cars are genuinely getting faster and more sophisticated with each generation, unlike some racing series where regulations create stagnation.

The Initiative Factor

What emerges most clearly from Cristina's story is the importance of initiative in motorsport engineering. From volunteering as a marshal to teaching herself programming to create her own data tools, every career breakthrough came from taking action rather than waiting for opportunities.

Her marshalling experience gave her unprecedented access: "I was the one handing out the penalties and stuff to the teams which was good in the sense that it allowed me to go to every other team and actually see from inside how they were working, what the engineers could be doing, mechanics and everything."

This willingness to take on unglamorous tasks, to learn new skills outside your comfort zone, and to create solutions when none exist – these are the qualities that separate good engineers from great ones. As Cristina puts it: "I think it's good definitely no matter which type of hands-on experience that young people come through [to] get those sort of less glam experiences to really answer the question as whether or not you think that is for you."

Final Thoughts

Cristina's career illuminates why Formula E engineering is such a fascinating discipline. It combines the precision of traditional motorsport with the flexibility demanded by emerging technology and unconventional circuits. The correlation challenges, data science innovations, and compressed timelines create a unique environment where quick thinking and adaptability matter as much as raw technical knowledge.

As Formula E continues to evolve towards Gen 4 and beyond, engineers like Cristina will play a crucial role in shaping not just race performance, but the future of electric motorsport technology. Her advice to younger engineers – "don't forget to enjoy it" – reminds us that even in this high-pressure, data-driven world, passion remains the ultimate fuel.

For aspiring motorsport engineers, Cristina's story offers a clear message: be ready to wear multiple hats, embrace uncertainty, and never stop learning. In Formula E, that mindset isn't just helpful – it's essential for success.