Adrian Newey has been drawing racing cars for decades. He's worked for some of the top teams in Formula 1, and the cars he's designed have, for the most part, utterly dominated the sport. But how did he arrive in F1? In today’s article, we’re going to take a look at that journey.

If you’re an aspiring Formula One engineer, budding aerodynamicist, or simply in awe of Newey’s work and hope to mimic his career in the future, this article is for you.

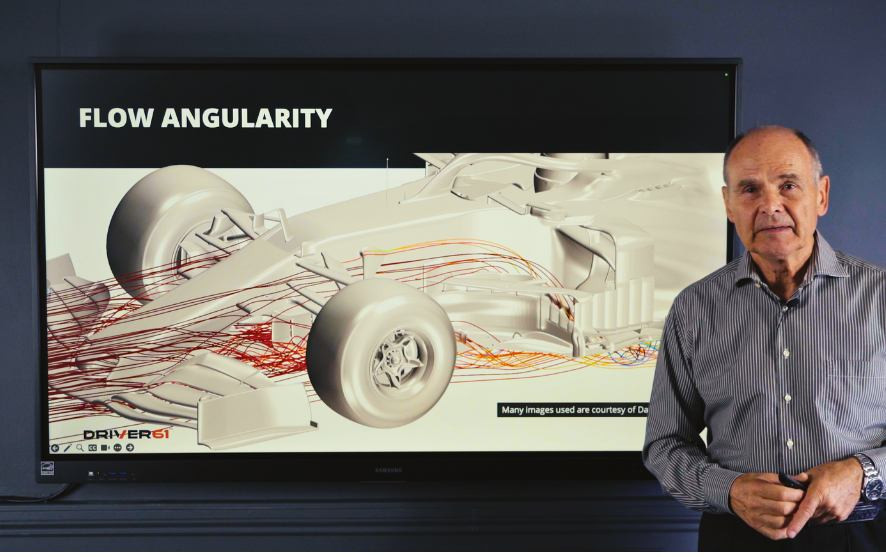

(Source: DRIVER61 - Adrian Newey's Formula 1 Design Secrets)

The Early Years: Growing Up and School Days

Newey was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1958. As a boy, he was keen on engineering and loved to understand how things worked. He would disassemble and reassemble mechanical objects in an effort to understand how they worked.

He is listed as a notable alumni of Repton School.

Newey went on to study Aeronautics and Astronautics at Southampton University, where he achieved a first-class honours degree. It’s reasonable to say that at the time, Motorsport engineering wasn’t a readily available course topic at university, and aerodynamics in Motorsport was still in its infancy. This educational grounding was to not just define Newey’s career, but redefine an entire genre of Motorsport in the years to come.

After graduating from Southampton University in 1980, Newey immediately looked for work in motorsport. He had a keen interest in racing and saw it as a field where he could apply his aerodynamics knowledge.

Adrian Neweys First Jobs in Motorsport

For his first F1 role, Newey joined the Fittipaldi Formula One team. He started as a junior aerodynamicist, working under Harvey Postlethwaite. This job gave him his first taste of F1.

After a year at Fittipaldi, Newey moved to the March team in 1981. At March, he initially worked on their Formula 2 project. He was a race engineer for Johnny Cecotto in European Formula 2. This role gave him valuable trackside experience as a race engineer, helping him understand how cars behave on track and how drivers interact with their machines.

It was at March that Newey got his first chance to design a complete car. His first design was a sports prototype car for the IMSA GTP class category in the United States of America. The March GTP car was successful, winning its championship.

(1982 March IMSA GTP 82 G ex Le Mans, ex Bobby Rahal, ex Paul Newman - Source: Classic Driver)

From there, Newey moved into designing IndyCars for March, which led to his successes in American racing before his return to F1.

The Return to Formula 1: Leyton House (formerly March)

Newey joined Leyton House (formerly March) in 1988. At this point, the team was still called March, but it was soon rebranded as Leyton House Racing in 1990.

When Newey arrived, he was given the role of chief designer. This was a step up from his previous positions and gave him more control over the car's overall concept. His first full F1 design was the March 881 for the 1988 season.

The 881 was quite a revelation. Despite the team's limited budget and asthmatic engine, the car was surprisingly competitive. The aerodynamic package of the car was a particular strength. In fact, at the 1988 Portuguese Grand Prix, Ivan Capelli managed to finish second in the 881, even briefly leading the race ahead of Alain Prost's McLaren.

March CG891

Newey's design philosophy at Leyton House was almost religiously dedicated to achieving the best possible aerodynamic efficiency. He created a very 'tidy' car with clean lines and a well-thought-out overall package. This approach would become a hallmark of Newey's designs throughout his career.

However, it wasn't all smooth sailing. The 1989 car, the CG891, was less successful. It suffered from reliability issues and struggled to qualify for races at times.

In 1990, now under the Leyton House name, things got tougher. The team faced financial difficulties, and the car's performance was inconsistent. There was a bright spot at the French Grand Prix, where Capelli nearly won the race, finishing second. But overall, the team was struggling.

Leyton House-Judd CG901 - (image source)

Midway through the 1990 season, Newey was fired from Leyton House. The exact reasons have always been unclear, but the stories imply there were disagreements on the team's direction. Newey later said that once the team started being “run by accountants rather than racers”, he knew it was time to move on.

Despite the difficult end, Newey's time at Leyton House was crucial for his career. It gave him his first chance to be a chief designer in F1, allowed him to develop his design philosophy, and showcased his ability to create competitive cars even with limited resources. The success of the 881 in particular, caught the attention of Patrick Head, leading to his move to Williams.

This period demonstrates how even in challenging circumstances, innovative design can make a difference in F1. It's a lesson that aspiring designers might take to heart - sometimes, working with a smaller team can provide opportunities to show your skills and creativity in ways that might not be possible in a larger organisation.

The Williams Years

Newey joined Williams in 1990, initially as chief designer. He'd caught the eye of technical director Patrick Head after the impressive performance of his Leyton House cars.

Williams FW14

His first full Williams design was the FW14 for the 1991 season. This car was quick but suffered from reliability issues which hampered their early season performance. Once these issues were resolved, the FW14 became competitive, winning races in the second half of the season.

The following year, 1992, saw the introduction of the FW14B.

Williams FW14b

This car was a game-changer. It featured active suspension, traction control, and anti-lock brakes. The FW14B dominated the season, winning 10 out of 16 races. Nigel Mansell took the drivers' championship, and Williams won the constructors' title. This period was a “golden era” of F1 where technologies such as active ride were playing a significant role in the success or failure of an F1 team.

In 1993, Newey's FW15C continued Williams' dominance. Alain Prost won the drivers' championship, and Williams again took the constructors' title.

The 1994 season was more challenging. New regulations banned many of the electronic aids that had made the previous Williams cars so dominant. Despite this, and the tragic loss of Ayrton Senna early in the season, the Williams FW16 was still competitive. The team managed to recover from such a terrible loss to win the constructors' championship with Damon Hill and David Coulthard, and when his IndyCar duties allowed, Nigel Mansell.

1995 saw Williams lose both titles to Benetton, but in 1996, Newey's FW18 helped Damon Hill win the drivers' championship and Williams to take another constructors' title.

Williams FW18

Throughout his time at Williams, Newey's designs were characterised by their aerodynamic efficiency and innovative use of technology. He worked closely with Patrick Head, forming a formidable technical partnership.

However, by 1996, tensions were growing. Newey wanted more control and to become technical director, but with Head being a shareholder in Williams, this wasn't possible. This led to Newey deciding to leave for McLaren.

Newey's Williams period showcases a few key points for aspiring designers:

1. The importance of pushing technological boundaries

2. How regulation changes can impact design philosophy and the importance of understanding the regulations in detail

3. The value of a strong technical partnership and teamwork (with Patrick Head)

4. The need to balance innovation with reliability

His time at Williams firmly established Newey as one of F1's top designers. The cars he designed during this period won numerous races and championships, setting the stage for the rest of his career.

After Williams, Newey moved to McLaren. Again, his cars were often the ones to beat. He was getting a reputation as the go-to designer for race winning F1 cars.

McLaren

Newey joined McLaren in 1997, but due to contractual obligations with Williams, he couldn't immediately influence the design of the 1997 car. Instead, he focused on the 1998 season.

1998 McLaren MP4/13

The 1998 McLaren MP4/13 was Newey's first full design for the team. It was a success right out pitlane. The car won the first race of the season and went on to dominate, winning both the drivers' championship with Mika Häkkinen and the constructors' title.

In 1999, Newey's MP4/14 helped Häkkinen secure a second drivers' title, although the team narrowly missed out on the constructors' championship.

The 2000 season saw a strong challenge from Ferrari, but the Newey-designed McLaren was still competitive, with Häkkinen finishing second in the championship.

Newey designed McLaren MP4/15 at Spa in 2000 - with *that* pass on Schumacher

One of Newey's most innovative - but ultimately unsuccessful - designs came in 2003 with the MP4-18. This car was extremely advanced but proved too complex and unreliable. It never raced, with the team using an updated version of the previous year's car instead.

Despite this setback, Newey's McLarens remained competitive, regularly challenging for race wins and podiums. However, they couldn't quite match the dominance of the Ferrari-Schumacher combination in the early 2000s.

During his time at McLaren, Newey continued to push the boundaries of F1 design. He experimented with novel aerodynamic concepts and was always looking for ways to exploit the regulations.

(image source)

By 2005, there were rumours that Newey was looking to leave F1 altogether. He had become somewhat disillusioned with the increasing restrictions on design freedom in the sport.

Newey's McLaren period demonstrates a few key points:

1. The challenges of adapting to a new team and new ways of working

2. The risks of pushing innovation too far (as with the MP4-18)

3. The importance of balancing performance with reliability

4. How competitive landscapes in F1 can shift over time

While not as dominant as his Williams era, Newey's time at McLaren further cemented his reputation as one of F1's top designers. His cars were always innovative and often among the fastest on the grid, even if they didn't always achieve championship success.

The Red Bull Racing Era

Newey joined Red Bull in 2006, attracted by the challenge of building up a relatively new team. At the time, Red Bull (previously Jaguar and prior, Stewart racing) was not a front-runner, but they had ambition and resources.

Image Source: Red Bull

His first full Red Bull design was the RB3 for the 2007 season. While not a race-winner, it showed promise and marked the beginning of Red Bull's ascent up the grid.

The breakthrough came in 2009 with the RB5. This car won six races and finished second in the constructors' championship. It showcased Newey's ability to adapt to major regulation changes, as 2009 saw a significant overhaul of the rules.

From 2010 to 2013, Red Bull entered a period of dominance. Newey's designs won both the drivers' and constructors' championships for four consecutive years. The RB6, RB7, RB8, and RB9 were all class-leading cars, with Sebastian Vettel at the wheel.

Red Bull RB6 (Image credit: Andrew Griffith)

The 2014 season saw another major regulation change with the introduction of hybrid power units. Red Bull struggled initially, largely due to issues with their Renault power unit. Despite this, Newey's chassis designs were still considered among the best on the grid.

In recent years, Newey has taken a step back from day-to-day F1 design, focusing more on special projects. However, he's still heavily involved in the overall concept of the cars.

The 2021 season saw a return to championship-winning form with the RB16B, which Max Verstappen drove, somewhat controversially, to the drivers' title. This was followed by dominant performances in 2022 and 2023 with the RB18 and RB19, winning both drivers' and constructors' championships.

Key points from Newey's Red Bull career:

1. The challenge and reward of building a team from midfield to champions

2. Adapting to multiple major regulation changes

3. Balancing chassis excellence with power unit challenges

4. The importance of a long-term vision and consistent development

Newey's time at Red Bull shows that success in F1 isn't just about designing a fast car, but about building a team, fostering a culture of innovation, and consistently adapting to changes in the sport by reading the letter of the regulations.

For young designers, Newey's Red Bull career demonstrates the value of committing to a project long-term, the importance of working well within a team structure, and the need to continually innovate even when you're at the top.

Newey’s Unique Working Methodology

Newey is known for considering the entire car as a complete package, rather than focusing on individual components. He aims to create cohesive designs where all elements work together harmoniously. This approach often leads to cars that are more than the sum of their parts.

Let’s take a look at how he prioritises aerodynamic performance and is well known to push engineering to its limit to accommodate aerodynamic performance.

Emphasis on Aerodynamics:

From his early days in IndyCar to his latest F1 designs, Newey has always prioritised aerodynamics. He often starts with the aerodynamic concept and builds the rest of the car around it. This focus has led to many innovations in how F1 cars manage airflow.

Hand-Drawing Technique:

Unlike many modern designers who rely heavily on computer-aided design (CAD), Newey prefers to sketch his ideas by hand on a drawing board. This old-school approach allows him to visualise the entire car and spot potential issues or opportunities that might be missed on a computer screen.

Pushing Boundaries:

Newey is known for his ability to find and exploit loopholes in regulations. He often comes up with innovative solutions that push the boundaries of what's allowed, forcing clarifications or changes to the rules.

Adapting to Regulations:

Throughout his career, Newey has shown a remarkable ability to adapt to changing regulations. Whether it's the switch to ground effect in 2022 or earlier changes like the introduction of grooved tyres, Newey often finds ways to gain an advantage under new rules.

Driver Collaboration:

Newey works closely with drivers to understand their needs and preferences. Perhaps as driver himself, he uniquely understands car setup and the balance required to make a car predictable and highly driveable. His collaboration with his drivers helps him create cars that not only are fast on paper but also suit the driving styles of top performers like Sebastian Vettel and Max Verstappen.

Continuous Development:

Newey's approach involves constant refinement and development of the car throughout the season. He's known for introducing updates that can significantly improve performance mid-season.

Problem-Solving:

When faced with challenges, like packaging issues or performance deficits, Newey often comes up with creative solutions. For example, his work on exhaust-blown diffusers at Red Bull showed his ability to turn a potential weakness into a strength.

For aspiring designers, Newey's approach underscores the importance of aerodynamics, thinking creatively about problem-solving, and perhaps most importantly, the ability to consider how different aspects of the car interact. It also highlights the value of hands-on involvement and close collaboration with drivers and other team members.

References and Further Reading

https://www.racecar-engineering.com/articles/f1/the-cars-of-adrian-newey/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrian_Newey

https://www.motorsport.com/f1/news/adrian-newey-leyton-house-march/4809839/